The case of Grant David Vincent Williams v. Jefferies Hong Kong Ltd illustrates how an employer can breach the implied duty of mutual trust and confidence that it owes to its employee in the way it treats that employee leading up to his summary dismissal. Although in Hong Kong an employee does not have the right to bring a claim for “unfair dismissal”, if the employer’s conduct towards the employee during employment leading up to a dismissal is irrational, this can be a breach the employer’s duty of mutual trust and confidence giving rise to substantial damages. In the Jefferies case the plaintiff employee was awarded damages in excess of HK$14 million and costs on an indemnity basis.

The Facts of the Case

The plaintiff, Grant Williams, was employed by the defendant company, Jefferies Hong Kong Ltd, as Head of Equity Trading Asia with the title of Managing Director on 26 August 2010. The plaintiff prepared a daily newsletter for the defendant company, which the defendant distributed to 900 or so subscribers as its publication. There was a protocol in place for vetting the newsletter which involved obtaining approval from an individual in London, before being distributed from New York.

A draft of the 7 December 2010 edition of the newsletter was emailed by the plaintiff to the personal assistant of the Head of Global Equities in New York in accordance with the approval protocol to await approval from London before being distributed. By error the personal assistant distributed the newsletter without having received approval from London.

The newsletter contained an incidental reference to the existence of a “Hitler video” without any comment save a warning concerning its use of many expletives.

Within 20 hours 44 minutes after the newsletter had been sent to London for review, the plaintiff was called to a meeting lasting a little more than 2 minutes where he was told that he was summarily dismissed for gross misconduct. The plaintiff was handed a letter that said he was summarily terminated “on the grounds of your unacceptable and entirely inappropriate misconduct. The detail of this has been discussed with you…”. (It was common ground at trial that no such discussion of detail had taken place.)

What Went Wrong?

The defendant had behaved irrationally in arriving at the decision to summarily dismiss the plaintiff.

The defendant had blamed the plaintiff for what was human error of the personal assistant, and made “irrational and patently unfair conclusions” (as the court described it) in deciding to summarily dismiss the plaintiff.

On the evidence the basis for the plaintiff ‘s summary dismissal was because the newsletter contained an inappropriate reference to Hitler and a reference to an inappropriate video known as the “Hitler video”. The inference drawn by the judge (because the relevant senior executives did not attend to give evidence) was that the senior executives were worried about the possibility that the CEO of JP Morgan might react to what might be perceived to be criticisms made by the defendant of him as a CEO in the financial world. The judge held that this line of thinking lacked logic, and that putting the responsibility on the plaintiff was irrational.

There was a misconception by one of the decision makers who decided to summarily dismiss the plaintiff (and possibly other decision makers as well, but they did not appear at trial to give evidence) that the plaintiff was the author or creator of the video. This was a fundamental error.

This decision maker said that the mere mention of Hitler’s name in the reference to the video concerned him and raised problems. The judge found that this reaction just did not make sense. Two witnesses for the defendant had declared in their witness statements that they considered the video racist and anti-Semitic, and that it appeared that the newsletter was propagating such, or at least condoning it. The judge held that it was not sensible or realistic to censor Hitler’s name out of a marketing publication, nor was it rational to suggest that the video, or the simple reference to it, denoted a “racist or anti- Semitic connotation”.

Shortly after the newsletter had been distributed, the defendant sent an email to its subscribers advising that they “inadvertently distributed Grant Williams’ December 7, 2010 edition…[of the newsletter] before it was properly vetted. That piece contained third-party material from a website that we do not condone”. This email contained a factual error in that “That piece” did not contain third-party material. Furthermore, the “material” was not distributed, but contained a reference to the existence of a piece of material. It was also described as “Grant Williams’… edition”. The judge said though Grant Williams was the editor/author, it was the defendant’s publication.

It was held that there had been an unreasonable effort to “tar” the plaintiff with overall responsibility because he was the creator or author of the newsletter, and its editor.

(It should be noted that those directly responsible for deciding on the plaintiff ‘s dismissal did not give evidence to explain or justify their decision, and were not subjected to cross-examination.)

The termination letter was regarded by the judge as evasive and possibly drafted deliberately without detail. The letter was presented at a meeting lasting two to three minutes in which the plaintiff was given no opportunity to understand the reasons for dismissal or put forward any argument.

It was held that the way the defendant handled the matter of the plaintiff ‘s dismissal, the explanatory email and the excision of the plaintiff from all contact and association with the defendant was in clear breach of the implied duty of mutual trust and confidence they owed to him. That implied duty is that an employer will not without reasonable and proper cause, conduct itself in a manner calculated and likely to destroy or seriously damage the relationship of confidence and trust between the employer and employee.

What Damages Did the Court Award to the Plaintiff?

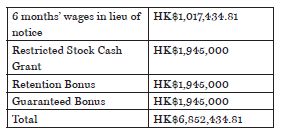

The judge awarded damages to the plaintiff under the following two broad categories totalling in excess of HK$14 million.

- Contractual loss of earnings and benefits

- Damages for breach of implied term of trust and confidence

- That the defendant sought to put the blame squarely on the plaintiff and tried to distance itself from the plaintiff by in effect denying that the newsletter was a corporate publication

- That the cessation of the daily newsletter would have been noticed by at least 900 subscribers and the immediate dismissal of the plaintiff would have been apparent to a wider audience

- That given the circumstances the audience may have queried whether there was something else behind the decision to dismiss the plaintiff which did not reflect well on him

- That an aggravating factor was the perception that the reference to the “Hitler video” somehow denoted racism, anti-Semitism and sexism

- That the plaintiff had problems obtaining alternative employment after his dismissal

- That the plaintiff was left with a stigma.

The court considered that the plaintiff would only be able to return to normality and gain worthwhile employment if he is free from the stigma attached to his dismissal and awarded the plaintiff damages for loss until 31 July 2013 as follows.

What Cost Award Did the Plaintiff Receive?

The plaintiff sought an order for indemnity costs. The judge considered that the defendant’s case at trial disclosed some extremely unpleasant features, and some important email communications were divulged very late into the proceedings. Further, in pursing the litigation, the defendant did not find a realistic “negotiator”, but instead found an unidentified member of the Jefferies group to respond to the plaintiff’s reasonable settlement proposals. The court found the defendant’s manoeuvrings to be wasteful and unconstructive.

The court ordered the defendant to pay the plaintiff’s costs on an indemnity basis which provides the plaintiff with a higher recovery rate than the scale of costs that is normally ordered.

What Are the “Take-away Points” for Employers?

In Hong Kong historically the typical remedy an employee can obtain from an employer who cannot demonstrate a valid reason for the dismissal of the employee is an order to pay “terminal payments” to the employee. Terminal payments are in effect unpaid statutory and contractual entitlements which the employer should have paid on termination of the employee’s employment.

The Jefferies case illustrates how substantial damages could be awarded to an employee for breach of an implied term during employment leading up to the dismissal.

Employers must be careful not to behave irrationally when dealing with an employee. That is, an employer should ensure that it has a rational and reasonable basis for taking action against or in respect of an employee.

Originally Published – 13 September, 2013

Visit us at www.mayerbrownjsm.com

Mayer Brown is a global legal services organization comprising legal practices that are separate entities (the Mayer Brown Practices). The Mayer Brown Practices are: Mayer Brown LLP, a limited liability partnership established in the United States; Mayer Brown International LLP, a limited liability partnership incorporated in England and Wales; Mayer Brown JSM, a Hong Kong partnership, and its associated entities in Asia; and Tauil & Chequer Advogados, a Brazilian law partnership with which Mayer Brown is associated. “Mayer Brown” and the Mayer Brown logo are the trademarks of the Mayer Brown Practices in their respective jurisdictions.

© Copyright 2013. The Mayer Brown Practices. All rights reserved.